If you’ve ever reread a workplace email and caught yourself typing “i’m so sorry” before you even know what you’re apologizing for, you’re not alone. In Canada, “sorry” can feel like a cultural handshake—an automatic softener we use to keep the temperature low in everyday interactions. From customer service interactions to internal Slack messages to tense social situations, apology language often shows up before a real problem does. The habit is so normalized that many apologizers don’t realize they’re doing it until someone points out how frequently they’re shrinking themselves mid-sentence. And even then, the reflex can be hard to break, because it’s often tied to identity, safety, and belonging—not manners.

This article is about over-apologizing (and Over apologizing, because it tends to show up in different forms depending on context). We’ll break down what “too much” actually looks like, why so many Canadians default to it, and what it quietly teaches the people around you about your self-worth. You’ll learn how constant “sorry” language can become a form of people-pleasing, a trauma response, or an anxiety-driven attempt to control outcomes through tone. We’ll also explore the professional and relational consequences of being chronically apologetic, and how to replace reflex apologies with language that preserves trust and helps you take up space.

If you want one grounded way to frame this before we go deeper, it helps to borrow a clinician’s lens—because this pattern is rarely just “a communication habit.” Here’s how our therapist sees it:

Here's what Zainib, our head therapist thinks about the topic generally.

It's pretty common for people who show people-pleasing tendencies to be judged harshly — seen as weak, not strong-minded, or unable to stand up for themselves. But actually, the reality is that it's just another manifestation of a defence mechanism, similar to many of the defences other people might have — for instance, being overly aggressive, highly contrarian, or passive-aggressive. People-pleasing is often simply a defence that helps our nervous systems feel safe. Maybe we've had histories where we needed to take care of people around us to gain a sense of safety, or where it wasn’t safe to share our views or thoughts openly. It can also relate to wanting to feel a sense of belonging or coping with feelings of shame. We may naturally develop this response over time.

In that sense, it can actually be a very wise nervous system response to situations that once felt threatening, especially when we were younger and didn’t yet have the ability to stand up for ourselves. Sometimes people-pleasing may also show up in people who are naturally shy or introverted, particularly in environments or cultures that don’t necessarily understand that. When a lot is being imposed on the system, these tendencies can develop as a way to cope.

There’s a reason “sorry” feels almost instinctive in Toronto, Vancouver, and everywhere in between: it’s social lubricant. In many Canadian environments—especially in polite, consensus-driven workplaces—apologizing is a shorthand for “I respect your time,” “I’m not here to cause conflict,” and “I’m safe to work with.” In fast-moving contexts, like high-volume retail teams in Calgary or hybrid tech orgs in Montreal, the apology becomes a tool for smoothing friction before friction even happens. The problem is that when a culture rewards smoothness more than clarity, apology language can evolve from courtesy into a behavioural default. And defaults, over time, shape reputation.

Ontario’s Apology Act, 2009 reinforces something subtle but powerful: saying “sorry” doesn’t necessarily mean you’re admitting liability. The law explicitly protects apologies from being treated as admissions of fault in many legal contexts, which encourages openness and de-escalation. You can read it directly here: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/09a03. But in everyday life, that legal nuance collides with a psychological reality: people still interpret repeated apologies as status signals. If your tone consistently says “I’m in the wrong,” you’ll eventually be treated like you are—whether or not you’ve done anything wrong.

At this point, most people assume the “fix” is just to catch yourself and stop.

Here’s a Zainib's take in plain terms:

I often explain to people that our nervous systems are not designed to make us happy — they are designed to help us survive. One of the most important survival needs human beings have is belonging and being accepted within groups, because so much of our survival depends on thriving in community. So when people-pleasing becomes a strong tendency or a reflexive pattern, it’s often because there has been a lot of wiring over many years — sometimes since early childhood — where someone needed to survive different kinds of stress or relational dynamics in order to be accepted, belong, be heard, or feel less guilt or shame. For some, this may come from being given too many responsibilities at a young age, needing to act as caretakers or people-pleasers without really understanding their own needs.

Because of this, the response becomes wired into the nervous system and naturally shows up in relationships. And when you think about it, we are in relationships all the time, so that wiring gets reinforced again and again over many years. It takes a lot of grace, compassion, and understanding to slowly soften these patterns — not necessarily to completely get rid of them, because part of us may always carry some history connected to this experience — but to gently work on softening their intensity over time.

Over-apologizing isn’t “being kind.” It’s apologizing when the apology isn’t connected to responsibility, repair, or accountability. A healthy apology shows awareness of impact, respect for the other person, and a willingness to change behavior. Constant apologizing, on the other hand, is often a reflexive attempt to manage someone else’s emotions in the first place—to reduce tension, avoid rejection, or prevent criticism before it arrives. It can sound harmless, but it changes the power dynamic in the room.

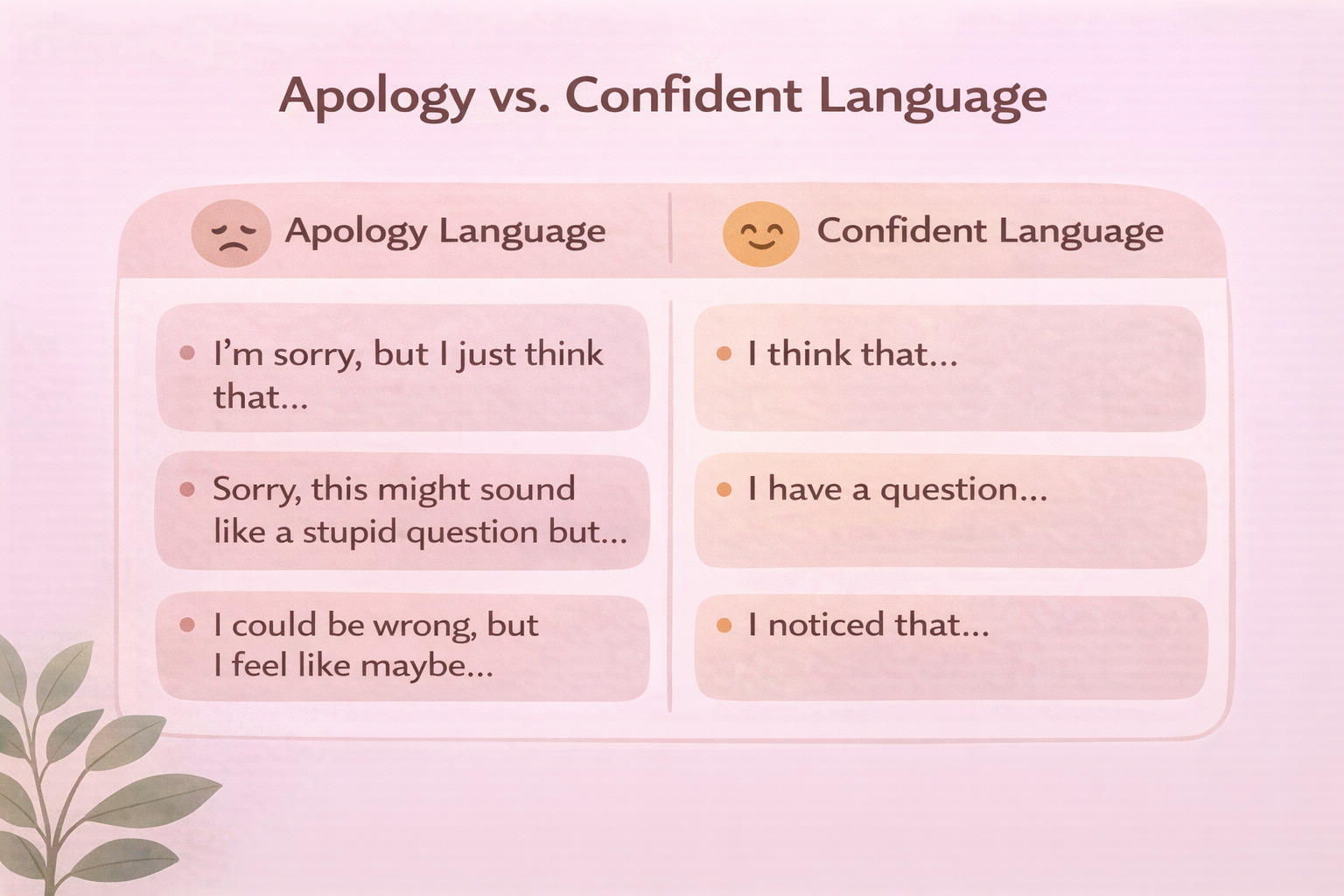

You’ll often see the difference in the “micro-apologies” Canadians overuse: “Sorry to bother you,” “Sorry, just a quick question,” “Sorry, but I think…” These phrases aren’t inherently wrong—but when they show up as a requirement to participate, they subtly communicate self-doubt, low entitlement, and a shaky sense of self. The apology isn’t doing repair; it’s asking permission to exist. That’s why over-apologizing is less about manners and more about psychology.

One reason this pattern becomes sticky is that apologies can quickly resolve discomfort. But when you repeatedly apologize for your presence, your questions, your needs, or your opinions, you’re reinforcing a belief that your contribution is “intrusive.” This can feed low self-esteem, amplify perfectionism, and create the kind of self-monitoring that makes overthinking feel unavoidable. In some clients, it also becomes part of a broader cycle involving people-pleasing, Validation seeking, and the belief that connection must be earned through compliance.

Psychologists have long discussed apologies as a social tool that can either repair trust or reinforce relational imbalance. The American Psychological Association has explored the psychology behind apologizing and why people do it (including when it’s not necessary): https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/apologize. That distinction—repair vs. reflex—is where over-apologizing begins.

To make the distinction sharper, it can help to step out of theory and into how this is understood in actual client work. Here’s how Zainib defines it day to day:

I think one way to help clients really understand what over-apologizing is versus what a healthy apology looks like is by attuning to their bodies. Once we become familiar with the pattern of people-pleasing and understand how that part of ourselves shows up, we can start to notice where it appears in our system. Oftentimes, it’s connected to feelings of anxiety or fear — especially a fear of disappointing someone — which can lead us to overlook our own needs.

Healthy apologies often involve considering our own need to stay aligned with our values and maintain self-respect, while also taking accountability and caring for the relationship we’re in. It’s about making sure we are accountable and open to repair. There’s always a balance. You might not feel great when apologizing or acknowledging that you’ve done something wrong, but you’re not hyper-focused on how the other person will react because you’re grounded in your truth in that moment.

The most obvious cost is confidence erosion. When someone apologizes for asking questions, sharing opinions, or needing clarity, they train themselves to believe their needs are “too much.” Over time, this pattern reinforces self-worth issues and creates a fragile relationship with competence: you can be talented, but still feel undeserving. That’s how constant apologizing quietly feeds low self-esteem, creates perfectionism anxiety, and makes every interaction feel like something you must “get right.” The person isn’t actually trying to be perfect—they’re trying to be safe.

Professionally, chronic apologies create a credibility tax. If you’re always softening, you start sounding uncertain even when you’re correct. Leaders who over-apologize can appear hesitant or hard to align behind—especially in decision-heavy roles where clarity matters more than courtesy. Canadian HR conversations increasingly emphasize direct communication because risk-averse language slows execution and weakens leadership signals; Canadian HR Reporter has discussed how leaders can become too risk-averse in communicating here: https://www.hrreporter.com/focus-areas/culture-and-engagement/are-leaders-too-risk-averse-in-communicating-with-employees/386882. The issue isn’t that apology is “bad.” It’s that constant apologizing can signal an unreliable internal compass.

Relationally, apology patterns shape expectations. If you constantly apologize to loved ones, you can unintentionally teach them that your boundaries are negotiable. In some relationships—especially with emotionally manipulative people or narcissists—your apology becomes a permission slip for someone else’s entitlement. Over time, you get resentment, passive-aggressive communication, and emotional distance that looks “fine” on the surface but feels increasingly unsafe underneath.

This is where the pattern stops looking like “politeness” and starts looking like a relational dynamic. Here’s how Zainib describes what often happens over time:

Over-apologizing can really impact how we experience closeness and relationships because when we feel shame or anxiety — like we’ve wronged someone in an interaction — we might start over-apologizing, or apologizing for things that don’t really need an apology. Over time, we can start losing a sense of respect for ourselves, and it just doesn’t feel good internally. That can also build a lot of resentment.

Sometimes people-pleasing and over-apologizing can lead to dynamics where others relate to us in ways that further minimize our needs, especially when we’re not speaking up or advocating for ourselves. So it can actually lead to feeling more hurt and resentful, and also create an imbalance in the relationship and in the sense of closeness.

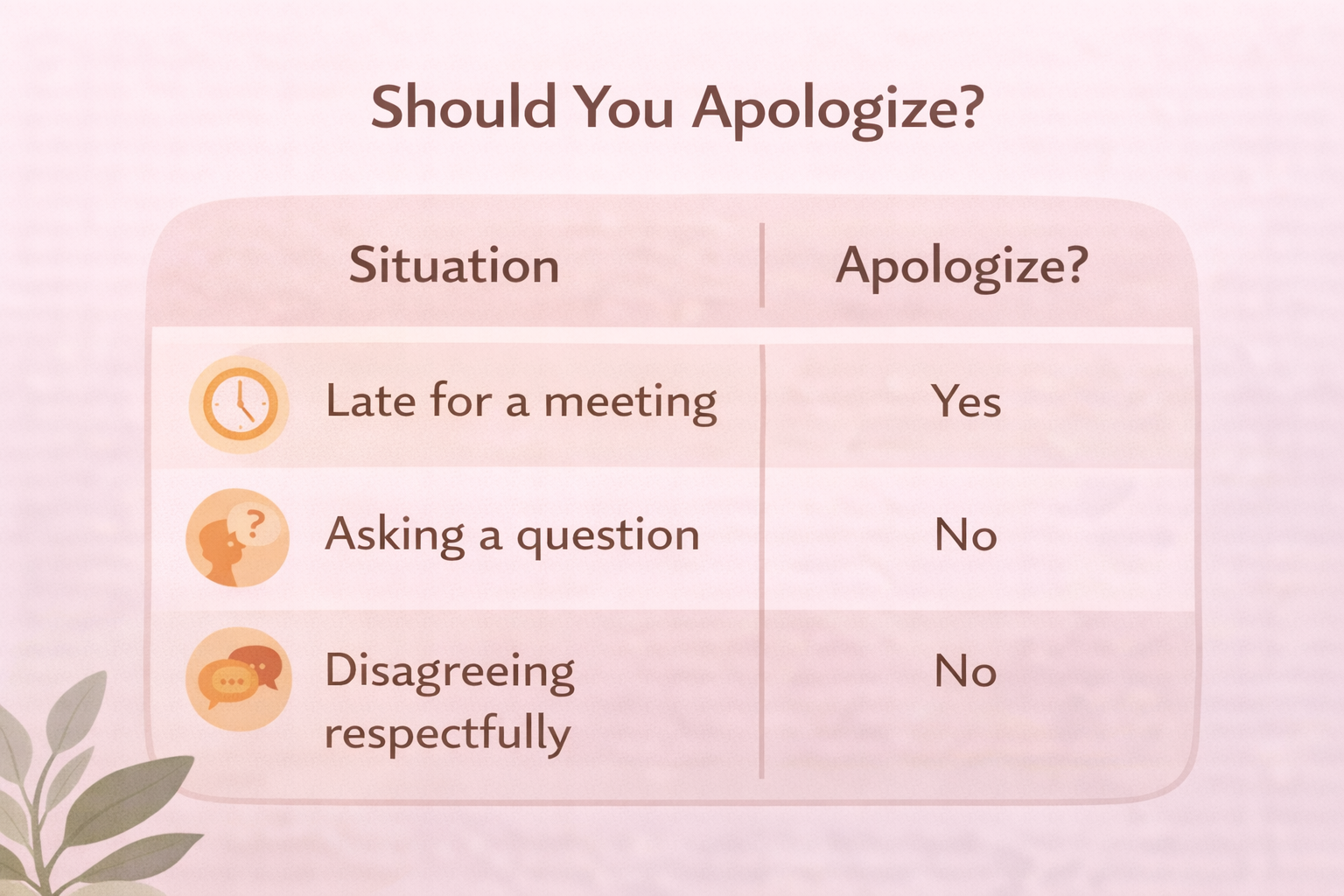

A good apology is a repair tool. It’s appropriate when you caused harm, made an error, violated a boundary, or created avoidable friction. But it’s not appropriate simply because you exist, need something, or have an opinion. That distinction sounds simple, yet it breaks down quickly when someone is stuck in people-pleasing patterns or lives with criticism sensitivity. In those cases, the apology isn’t connected to ethics—it’s connected to fear.

When apologies become reflexive, they often masquerade as politeness while functioning like a coping mechanism. That coping mechanism can show up as conflict avoidance, a shutdown response, and even “agreeing too quickly” to avoid tension. In the short term, this keeps relationships calm. In the long term, it produces misalignment, emotional exhaustion, and the subtle resentment that comes from consistently abandoning yourself.

Even with simple guidelines like these, many people still feel uncertain in the moment—especially under stress.

Most people assume the goal is to stop apologizing entirely. It’s not. The goal is to stop apologizing as a substitute for self-trust. If you remove apologies without replacing the underlying need—belonging, safety, certainty—you’ll just become tense, brittle, or avoidant. What works is building a new set of language habits that preserve warmth while restoring authority.

Start with “intent-preserving swaps.” Replace “Sorry to bother you” with “Thanks for your time,” and “Sorry, but…” with “I’d like to suggest…” This works because gratitude communicates respect without implying wrongdoing. It also reduces boundary setting struggles, because you’re no longer asking permission to have needs—you’re stating them with calm confidence. You can still be kind without shrinking.

Then address what happens in the body. Over-apologizing spikes during Decision fatigue, stressful social moments, or periods of Emotional flooding where your nervous system feels overwhelmed. When that happens, apologizing becomes an emergency release valve. If you notice your sorry-reflex rising at the end of a day, after a difficult customer call, or mid-conflict, don’t treat it like a character flaw—treat it like data. It’s often paired with emotional exhaustion, doomscrolling psychology, and the quiet internal panic of worst case scenario thinking.

If you want something practical that doesn’t require changing your entire personality, this is a good place to start. Here’s one tool Zainib often recommends in-the-moment:

A practical technique that we usually work with is actually working with your body — noticing what it feels like to have an upright spine, to gently tuck in your core, and to use grounding techniques like placing a hand on your chest or your belly as a form of weight and support, while feeling the firmness of the floor underneath you as you speak. Sometimes you can sit against a wall to start exploring what that posture feels like. But more importantly, how do we breathe? How do we slow the activation down when we feel like we’re risking rejection? That can really help us.

And then, how do we start turning toward ourselves and speaking to the shame or the fear of being abandoned? How do we locate that in our body, turn toward it, and literally speak to it — like, “I see you. I see how protective you are for me. I don’t need you right now. I’m going to practice leading with my values, or practicing courage and curiosity.”

Over-apologizing becomes especially visible in Canadian corporate settings because the culture often values harmony over tension. In remote and hybrid work, the missing context of tone makes it worse—people overcorrect by softening everything “just in case.” That’s why apology phrases explode in email threads: it’s a way to reduce ambiguity and protect relationships. But it’s also how high performers quietly sabotage their own authority.

DEI and multicultural environments add complexity. But the break point is when apology becomes the price of participation—when you feel you must apologize to contribute ideas. That’s where you’ll see self sabotage signs, prolonged rumination causes, and the slow confidence erosion that leads to invisible burnout.

Workplaces that value psychological safety don’t punish directness—they teach it. They normalize asking questions without apology and giving feedback without emotional theatre. Without that, teams slip into difficult conversation avoidance, and performance problems turn into culture problems. Eventually, people start disengaging through quiet quitting mental health patterns, because it becomes easier to shrink than to keep fighting for space.

In client work, this pattern shows up most often in the people you’d least expect—high performers who are already carrying a lot.

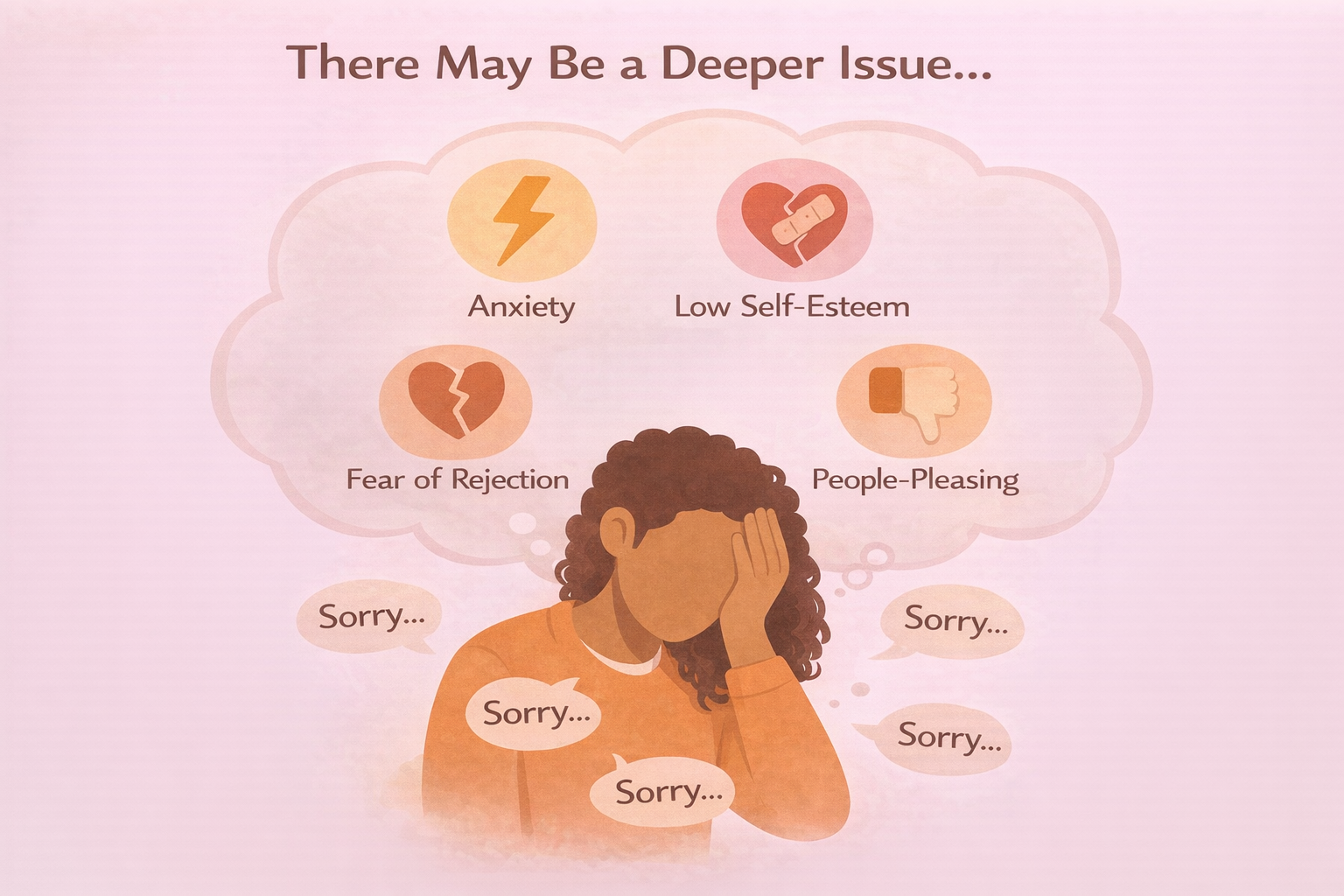

Sometimes over-apologizing is just a habit. But often, it’s a symptom. It can be linked to anxiety, trauma learning, ADHD-related rejection sensitivity, or the aftereffects of relational instability. It can show up alongside relationship anxiety, abandonment anxiety, and patterns shaped by attachment style psychology. People who grew up around unpredictable criticism often become hyper-attuned to micro-signals, and apologies become a way to pre-empt rejection.

It can also show up in high-functioning profiles that mask internal strain: high functioning anxiety and high functioning depression. Externally, the person looks capable; internally, they feel depleted and emotionally split. They may report emotional numbness, a chronic slow burn breakdown, and the strange loneliness that comes from always being “fine.” When someone is carrying the emotional burden of being the strong one, apologizing can become a way to keep everyone else regulated—at the cost of their own well-being.

If you recognize yourself in that, help doesn’t need to be dramatic or permanent. Many people benefit from online therapy, especially if they want targeted support for confidence, boundaries, and anxious relational patterns. Evidence-based approaches like cognitive behavioural therapy are commonly used to treat anxiety and related mental health patterns, and CMHA Ontario has resources on anxiety support here: https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/understanding-and-finding-help-for-anxiety/. The point isn’t to pathologize apology. It’s to understand what it’s protecting you from.

For some people, this is just one small habit to unlearn. For others, it’s the surface expression of something bigger. Here’s a gentle way Zainib talks about that distinction:

If you’re struggling to understand what your needs are or how to communicate them, and you feel a lot of anxiety or stress around expressing yourself, you’re not alone. It’s a skill that can be learned, and the feelings that come with it can also be managed and reduced. The early memories connected to these experiences can be processed too.

Professional support can be really helpful when this starts interfering with your day-to-day life, or when there’s a high level of emotional intensity that feels hard to manage and is impacting your relationships.

Over-apologizing isn’t a personality flaw—it’s a pattern. And patterns can be rewritten. When you stop paying for belonging with constant apologizing, you’ll often notice something surprising: people don’t respect you less. They trust you more. And in a culture where “sorry” is everywhere, learning to speak without shrinking is one of the most powerful forms of self-respect you can practice—short term, and for the long haul of your well-being.

To close on something practical and compassionate: it helps to remember that this isn’t about never apologizing again—it’s about rebuilding your relationship with your own voice. Here’s one final thought from Zainib:

What a reminder is to be compassionate with yourself and see this response as a self-protective response that you could turn to with curiosity or turn towards with curiosity and a desire to understand how it protected you at a point in time and why it's not helping you at this time, but that you need grace and time and that healing is not a linear process, but you are an individual experience.

It often means they’ve learned emotional safety comes from keeping other people comfortable, even at their own expense. For some, constant apologizing is tied to people-pleasing psychology, low self-esteem, and a fragile sense of self-worth where participation feels like something they must earn. It also commonly appears in social anxiety and anxiety disorders, where uncertainty in social situations feels threatening and apologizing becomes a safety behavior. Over time, the person may become emotionally exhausted, stuck in overthinking psychology, and increasingly unable to take up space without guilt.

A clinician would often describe this less as “too polite” and more as “too responsible for everyone else.” Here’s how our therapist explains it:

Respond in a way that reduces shame while reinforcing steadier communication. You can validate their intent (“I know you’re trying to be considerate”) while also removing the need for apology (“you don’t need to apologize for asking”). This helps interrupt validation seeking loops without making the person feel criticized. If you respond with irritation, it often increases rumination causes and makes the person more apologetic in future social situations.

Yes, apologizing a lot can be a trauma response—especially if someone learned that conflict led to punishment, withdrawal, or emotional volatility. In that context, apologizing becomes a pre-emptive strategy to prevent harm, not a reflection of actual responsibility. It’s often paired with shutdown response patterns, abandonment anxiety, and conflict avoidance. People may also become emotionally numb over time as a way to cope with the constant relational vigilance.

It depends on what the apology is doing. When it’s occasional and sincere, it can signal humility and emotional accountability. But when someone is chronically apologetic and uses apologies to avoid direct truth, it can create trust issues. In some cases, it can mask difficult conversation avoidance and build into passive-aggressive communication or emotional exhaustion.

Most people aren’t overly apologetic because they’re weak—they’re trying to stay safe. Over-apologizing often emerges from perfectionism anxiety, criticism sensitivity, and worst case scenario thinking where the brain rehearses rejection in advance. It also overlaps with adhd (especially rejection sensitivity), and relationship anxiety in emotionally unpredictable environments. If you find yourself constantly apologizing, it may be less about manners and more about boundary setting struggles.

People over-apologize because it works in the short term. It reduces tension quickly and signals submission or agreeableness, which can feel safer in uncertain social situations. But the long-term cost is increased overthinking, reduced self-worth, and the slow burn breakdown that comes from constantly editing yourself. Over time, it can also lead to social burnout, loneliness symptoms, and emotional numbness.

Supporting loved ones starts with consistency: check in, stay connected, and don’t pressure them to “perform wellness.” Depression can present differently depending on the person and their circumstances—some experience high functioning depression where they still show up externally, while internally they’re dealing with emotional exhaustion and feeling stuck in life. Others show more visible withdrawal, loneliness symptoms, and loss of motivation. If they’re apologizing constantly while saying they’re “fine,” it may be a sign they’re carrying invisible burnout and the emotional burden of being the strong one.

For additional context, CAMH offers general resources on depression here: https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/depression.

It can be, especially if apologizing helps someone avoid anger, abandonment, or shame. In trauma-shaped patterns, apologizing becomes a form of trauma response independence—“if I take responsibility for everything, I stay safe.” It often overlaps with trust issues, psychology and abandonment anxiety, because the person feels they must continuously prove they are not “too much.” Over time, this can create emotional exhaustion, emotional numbness, and shutdown response patterns.

Over-apologizing becomes passive-aggressive when it contains a hidden accusation or guilt-hook. For example, “Sorry I’m such a burden” isn’t a repair attempt—it’s self-criticism that pressures the other person to reassure you. This dynamic can create emotional flooding in relationships because it makes communication feel unsafe and manipulative. Over time, it drives conflict avoidance and makes difficult conversations harder, not easier.

Yes—anxious overthinking affects your social life because it shifts your attention away from connection and toward threat scanning. This can lead to rumination causes, rehearsing fake scenarios in your head, and replaying social situations long after they end. It can also cause productivity anxiety, where you treat every interaction like a performance metric. Over time, the result is social burnout, loneliness symptoms, and a decreased sense of self.

Infidelity often amplifies existing mental health conditions by triggering attachment wounds and abandonment anxiety. Even people who typically cope well may experience emotional flooding, emotional numbness, and shutdown response patterns when trust breaks. If someone already struggles with over-apologizing, they may take responsibility too quickly, which creates relational imbalance and blocks true repair. In these situations, support—sometimes through online therapy—can help rebuild boundaries, clarity, and self-worth.

Start by noticing your triggers: decision fatigue, conflict, uncertainty, and criticism sensitivity. Then replace the apology with an intent-preserving phrase that keeps warmth but restores self-worth (“Thank you for your patience” instead of “Sorry I’m late”). If the pattern is tied to anxiety disorders or trauma response learning, cognitive behavioural therapy can help because it targets the thought loop behind the behavior, not just the words. CMHA Ontario has anxiety support resources here: https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/understanding-and-finding-help-for-anxiety/.

Over-apologizing is often driven by people-pleasing, low self-esteem, fear of rejection, and conflict avoidance. It can also be part of overthinking psychology, where the brain tries to control outcomes through tone, leading to worst case scenario thinking and rumination causes. Many clients also experience emotionally unavailably partners, which can intensify relationship anxiety and make boundaries feel risky. In those cases, apologizing becomes a strategy to maintain closeness—even when it harms self-worth.

[Some of these images were generated with ChatGPT's DALL-E]